|

By Suncoast News

LAND O LAKES – The Area Agency on Aging Pasco-Pinellas is reminding residents that their Serving Health Insurance Needs of Elders program has specifically-trained counselors to help educate and empower Medicare beneficiaries, their families and caregivers to understand their health care options so they can make the best decisions for their individual needs during the Open Enrollment period. During open enrollment, beneficiaries can change their Medicare Prescription Drug or Medicare Advantage plan to effect things like cost, coverage, drug formularies, in-network providers, and pharmacies. “Medicare can be a daunting subject for most people and the Open Enrollment Period only runs from Oct. 15, 2023, through Dec. 7, 2023, but you don’t have to go it alone. During this time, lean on our experts for advice and utilize a local, valuable resource by connecting with the SHINE program,” said Ann Marie Winter, executive director. SHINE is a program of the Florida Department of Elder Affairs and is operated locally through The Area Agency on Aging Pasco-Pinellas. The SHINE mission is to provide free and unbiased information about Medicare and Medicaid for beneficiaries, their families, and caregivers. SHINE also educates beneficiaries to protect, detect, and report potential errors, fraud, and abuse with their Medicare coverage. SHINE strongly encourages beneficiaries to be on the lookout for their Annual Notice of Change, which they should receive from their plan no later than Sept. 30, 2023. Reviewing their benefits and evaluating their health care options each year is vitally important for beneficiaries. Acting quickly can assure a smooth transition into the 2024 benefit year. To receive help from SHINE, individuals may call to schedule appointments at designated SHINE counseling sites, attend enrollment events in their local communities, or arrange to speak with a trained SHINE counselor at 1-800-96-ELDER (1-800-963-5337). For a listing of SHINE counseling sites and enrollment events, visit www.floridashine.org.

0 Comments

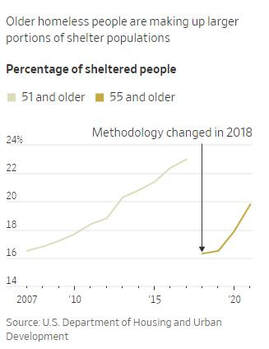

The aging of America means more old people on fixed incomes are overwhelmed by the high cost of housing and other financial shocks; ‘not seen since the Great Depression’ By Shannon Najmabadi Sept. 12, 2023 10:00 am ET  NAPLES, Fla.—Judy Schroeder was living a stable retirement in this affluent Florida enclave. Then her apartment building was sold to a new owner during the pandemic and she lost her part-time job working at a family-owned liquor store. What followed was a swift descent into homelessness. Faced with a rent increase of more than $500 a month, Schroeder, who had little savings and was living month-to-month on Social Security, moved out and started couch surfing with friends and acquaintances. She called hundreds of other landlords in Naples and southwest Florida but failed to find anything more affordable. She applied for a low-income housing voucher. She began eyeing her 2004 Pontiac Grand Am as a last resort shelter. “I never thought, at 71 years old, that I would be in this position,” she said. Baby boomers, who transformed society in so many ways, are now having a dramatic effect on homelessness. Higher numbers of elderly living on the street or in shelters add complications and expenses for hospitals and other crisis services. The humanitarian problem is becoming a public-policy crisis, paid for by taxpayers. Aged people across the U.S. are homeless in growing numbers in part because the supersize baby boomer generation, which since the 1980s has contributed large numbers to the homeless population, is now old. But other factors have made elderly people increasingly vulnerable to homelessness, and the vast numbers of boomers are feeding the surge. High housing costs—a major factor in all homelessness—are especially hard for seniors living on Social Security who are no longer working. Low-cost assisted living centers, never built in adequate numbers to handle the larger baby-boom generation, have been closing amid staffing shortages and financial troubles, and society’s dispersal of families means less support for older people. The second half of the baby boomers, now mostly in their 60s, unlike the older members of their generation, came of age during back-to-back economic downturns, permanently setting them behind in wealth, according to some academic researchers. Many of them worked jobs that had stopped offering pensions. Those “trailing edge” boomers who are financially less secure are now mostly moving into retirement. “The fact that we are seeing elderly homelessness is something that we have not seen since the Great Depression,” said Dennis Culhane, a University of Pennsylvania social policy professor and researcher with expertise in homelessness and housing issues. ‘Silver tsunami’ Officials with the Department of Housing and Urban Development say older adults are the fastest-growing segment of the homeless population and are making up a larger and larger share of homeless people overall. HUD will for the first time break down how many homeless people are 65 and older across the country in its annual tally of the national homeless population released around the end of the year. In previous data from HUD, which isn’t as extensive, people 51 and older were 16.5% of people in shelters in 2007 and 23% in 2017—a rise steeper than that of the overall senior population during that time. The federal government changed the way it tracks data around that year, but the increase has continued. People 55 and older were 16.3% of the sheltered homeless population in 2018 and 19.8% in 2021, federal data show. Metropolitan areas including Miami, Denver and Columbus, Ohio, have recorded steep increases in homelessness among older people, illustrating what many experts say is a mounting “silver tsunami.” The aging population has strained shelters ill-equipped to accommodate wheelchairs or people unable to climb onto top bunks, according to shelter staff. Culhane and other researchers estimated in one study that healthcare and shelter costs in New York City would roughly triple by 2030 compared with 2011, and in Los Angeles would go up 67%, as the older homeless population, who are generally in poorer health, visit emergency rooms, are hospitalized or stay in nursing homes. A large portion of older adults now homeless have lived on and off the streets or in shelters during younger phases of their lives, often with mental illness or drug addiction. The experience leaves them at age 58 with the physical health of the average 70- or 80-year-old, according to a 2016 University of California, San Francisco study. But researchers said about half of the homeless older adults they spoke to in Oakland, Calif., New York and elsewhere were unhoused for the first time after their 50th birthday and can point to a precipitating event that destroyed what had previously been a relatively comfortable life. Those newly homeless were more likely to cite the death of a spouse or a medical emergency as the cause, and they often felt shocked—even betrayed—that they were homeless after thinking they had done everything right to earn a decent retirement, homeless advocates said. “It’s an entirely different population,” said Margot Kushel, a University of California, San Francisco researcher who co-authored the 2016 study covering Oakland. “These are people who worked their whole lives. They had typical lives, often working physically demanding jobs, and never made enough to put money away.” Rising rents A shortage of homes in the U.S., caused by factors including the 2008 real-estate crash and building restrictions such as prohibitions on multifamily dwellings, has helped drive up rents. The pandemic further tightened the supply, as urban dwellers relocated, taking advantage of low mortgage rates at the time. Supply chain disruptions also hampered efforts to build. Among the 20 metro areas that saw the steepest rent increases between January 2020 and June 2023, 10 were in Florida, according to available Zillow data. The state has no rent control laws, and it saw an influx of out-of-state renters and home buyers in recent years who drove up demand and prices. In Naples, a typical rental cost $2,833 in July, according to Zillow data. The average Social Security payment for retired workers and their dependents that month was $1,791, according to federal data. The elderly often have limited mobility or funds to move to cheaper areas, or don’t want to leave a doctor and friends they know. The number of homeless seniors counted on one night, a common way to assess the homeless population, rose from 59 in 2018 to 195 in 2023 in Collier County, which includes Naples, according to data collected by the Hunger & Homeless Coalition of Collier County. Florida needs about 400,000 more low-cost rental units to meet demand, according to a 2023 analysis by the University of Florida’s Shimberg Center for Housing Studies that looked at 2021 American Community Survey data. “You can imagine, the minute a car breaks down, someone misses work, there’s an illness, it puts you at immediate risk of homelessness,” said Don Anderson, president of the Florida Coalition to End Homelessness. In 2021, Schroeder learned she had to move out of her two-bedroom apartment because a new building owner was planning to renovate and then substantially increase the rent. The new owner let her stay a few extra months, paying $1,399 for monthly rent instead of $875. She moved in with a friend who was going blind, acting as a caregiver to him and his son, who had mental illnesses, in exchange for rent. Schroeder doesn’t have children and said her husband died from cancer in the 1990s. In September 2022, Hurricane Ian battered Florida’s west coast, flooding the home where she was living. Her friend and his son moved in with another family member. Schroeder stayed briefly with another friend and then returned to the flooded home for two weeks, sleeping on a mattress until she got pneumonia. On the advice of an acquaintance she then moved into a small apartment with a woman who she said turned out to be frightening and verbally abusive. Schroeder said she spent each day hunting for a place to live. She applied and was approved for a Section 8 housing voucher, in which she would pay about 30% of her income for rent at a qualifying property and a federal subsidy would cover the rest, but couldn’t find an open spot. She put her name down on waiting lists where she could, and called day after day to other places to see if anything had opened up. “It’s a full-time job,” she said. “I was on the phone seven to eight hours a day, calling, calling, calling, calling and then re-calling.” Florida landlords in high-demand areas often require that a renter’s income be three-times rent. “Rent for me through the years has always been 50% to currently 76% of my monthly income,” said Yvonne Tyno, 69, whose Tampa apartment was sold to a new owner in 2021. “Even with a perfect rental history, perfect credit score and some savings that was not enough.” Tyno ended up living in her 1999 Jeep Grand Cherokee, sleeping at rest areas along Interstate 75 in Florida—choosing places that had 24-hour security. She said she saw many older people doing the same thing, living with all their possessions, including dogs and cats, in their cars. “Every day we would just move usually 33 miles south or north on I-75 to another rest area,” she said. “When I found a truck stop where I could buy a shower I was thrilled.” After driving from Florida to New Mexico looking for housing, she found an apartment in New Orleans. Waiting lists Volunteers of America of Florida said five of their 11 low-cost buildings for seniors each have 100 people on waiting lists, and the remaining six each have 500 people on waiting lists. “The reason we don’t have more is because HUD asked us to stop accepting applications” for the list, said Janet Stringfellow, the chief executive officer of the nonprofit organization in Florida, which owns and operates housing that takes Section 8 vouchers. There is a similar scarcity in long-term-care facilities. In Pasco and Pinellas counties, near Tampa, about 2,600 seniors are on the waiting list for long-term care paid for by Medicaid, according to Ann Marie Winter, executive director of the local Area Agency on Aging. In comparison, the median price of a room in a private nursing home in Florida was $115,000 a year in 2021. Shelters are filling the role of nursing homes without medical staff, said Steve Berg, chief policy officer with the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “If somebody needs help bathing, are there people who work at the homeless shelter who are trained to do that?” Berg said. “Probably not.” St. Matthew’s House, a shelter in Naples, does a medical screening as soon as someone arrives and will sometimes call emergency medical services right away, said Kelsey Couture, a shelter and housing director. The organization said it provides walkers and wheelchairs to unhoused seniors living there, and that younger residents will sometimes help elderly residents. Still, adults should be able-bodied to reside in their shelter, Couture said. “It does pose a liability for us,” she said. “They can easily have a slip-and-fall.” Seniors are less likely to ask for assistance than younger homeless people, advocates said. “They are reluctant to go to their family, friends or even admit that they’re in this situation, oftentimes until it’s too late,” said Anderson, the Florida Coalition to End Homelessness president. Bruce Kennedy, 72, an Army veteran who later became a caregiver, school bus driver and then a security guard, resorted to living at St. Matthew’s House after his car broke down, forcing him to take ride-shares to work. The added cost made him unable to afford his rent, he said. His arthritis was also making it hard for him to stay on his feet, he said. He eventually moved to a house meant for recovering addicts, despite having no history of abusing drugs or alcohol, sharing a room for $600 a month. He paid for it with Social Security. He has two adult sons he hasn’t seen in person since the 1990s. He said it has been too expensive to travel to visit them in Virginia. “The worst phone call would be to say ‘I’m going to be homeless, could you guys let me stay in your house?’” said Kennedy. “People suggested I do that, but I just couldn’t bring myself to.” Wounded Warriors of Collier County, an organization that has purchased Naples-area homes to house local veterans, helped Kennedy move out of the recovery house and into one he now shares with two other formerly homeless veterans. One of them stayed in the same homeless shelter Kennedy did after he lost his job as a dishwasher and was evicted during the pandemic. The typical veteran the group helps is 72 and has an income between $1,000 to $1,100 a month, said Dale Mullin, the group’s founder, who said he has seen homeless numbers increase. “A one-bedroom apartment in Collier County now is a minimum of $1,800,” he said. Nowhere ‘to put them’Mitch Watson, who works at the Hunger & Homeless Coalition of Collier County, said many of the seniors he assists belong in a more advanced medical facility. In recent months he has helped a 79-year-old former real-estate agent who struggled to remember aspects of her own background and an 81-year-old veteran with a walking stick who was living in his 2022 Nissan Rogue. “I don’t have anywhere to put them,” Watson said. Life on the street can be extra difficult for older people, who might need daily medicine or an oxygen machine, said Thomas O’Connor Bruno, chief operating officer of the Coalition for the Homeless of Pasco County. They’re also vulnerable to theft or abuse. Duane Edward Winn and Barbara Throckmorton, ages 55 and 63, wandered the streets of Pasco County, north of Tampa, when they first became homeless last October, unsure where to go. They said their rent check was stolen and they didn’t find out until shortly before they were evicted. Throckmorton was turned away from a local homeless shelter because the only beds available were top bunks, which people 60 and older aren’t allowed to use, she said. The pair slept on empty sidewalks for two nights, their bodies aching each morning. They shared one blanket. “I thought I was going to die,” Throckmorton said, as she sat by the couple’s tent. Throckmorton has received about $900 a month in disability payments since she was in a car accident in the 1990s. Winn is applying for disability because he broke five ribs and has osteoporosis that has left him unable to continue working as a general contractor. They were receiving $280 a month in food stamps but didn’t have a refrigerator, requiring them to buy nonperishable foods and ice each day. At first, the couple was confident they would quickly save up enough to get off the streets. But their optimism was dashed as they kept having to replace stolen items. Both their cellphones were taken. A heater they bought was stolen before they could use it. Schroeder, the woman who had pneumonia, moved to the home of another friend earlier this year. That friend died soon after Schroeder moved in, and she bequeathed the house to a woman who kept hinting that Schroeder needed to find somewhere else to stay. She spent two months sleeping on a couch on the glassed-in back porch of the house. Finally, Schroeder was kicked out. In June, she moved to stay with another friend who said he could accommodate her for 10 days, and then to a third friend’s one-bedroom apartment, where she slept on an air mattress. At that point she had moved multiple times in nine months since the hurricane and was becoming desperate. “I’ve gone out on a limb and really expanded my network,” she said at the time. “I don’t know what’s going to happen.” In late August, Schroeder found an apartment, a clean but rundown unit with painted cement-block walls and speckled gray flooring, in a rural area northeast of Naples in a complex called Farm Worker Village. She burst into tears of relief when saw it, the day she moved in. She pays 30% of her Social Security income in rent, with the federal Section 8 subsidy covering the rest. She has asked about a job at the local Dollar General store. She said she might pawn some of her belongings to pay bills until her next Social Security check comes in. “I’m not moving again,” she said. “I can’t even think of it…I’m going to be here until the good Lord wants me.” More than 48 million Americans provide care to a family member so they can live independently, and it can be a tough job. They’re tasked with medical care, cooking meals, bathing their loved ones and providing transportation. “This is Ernie’s senior year picture. A pretty dapper-looking dude,” said Yvonne Casares, looking at old photos of her husband. Yvonne is a caregiver to her husband, Ernie. Ernie has Parkinson’s disease and dementia. “And there’s no cure. There’s nothing you can do. He’s very forgetful,” said Yvonne. By: Anthony Hill Posted at 10:27 AM, Sep 08, 2023 and last updated 5:32 PM, Sep 08, 2023 TAMPA, Fla. — More than 48 million Americans provide care to a family member so they can live independently, and it can be a tough job. They’re tasked with medical care, cooking meals, bathing their loved ones and providing transportation. “This is Ernie’s senior year picture. A pretty dapper-looking dude,” said Yvonne Casares, looking at old photos of her husband. Yvonne is a caregiver to her husband, Ernie. Ernie has Parkinson’s disease and dementia. “And there’s no cure. There’s nothing you can do. He’s very forgetful,” said Yvonne. It’s far from an easy job. “Trust me, there are times whenever you just have lost all patience and you say, ‘Okay, I’m done. I need 15 minutes. Sit there, don’t get up,' and you go and just kind of chill for a minute,” said Yvonne. Due to how expensive long-term care facilities can be, Yvonne does this 24/7 job herself. “You do it because you love them,” said Yvonne as she began to get overwhelmed with emotion. It’s estimated that there are about 2.7 million caregivers in Florida. “Often, what we hear from caregivers is that they had to take time off from work and sometimes step out of the workforce to provide care for an aging parent,” said Jeff Johnson with AARP. Johnson said those caregivers provide $40 billion a year in unpaid services. “Unpaid caregivers are the unsung heroes of our modern society,” said Ann Marie Winter with the Area Agency on Aging of Pasco-Pinellas. They provide services to caregivers like respite care so that caregivers can get out of the house and have a little free time. They also have support groups, but there’s a waitlist for many of their services. “Reach out to us before they need those services. Get on that waitlist so that when a spot does become available, they can access the service,” said Winter. “Caregivers frequently, the research shows, pass away before the loved ones that they’re caring for because they’re not taking time to care for themselves,” said Katie Parkison, who is with the Senior Connection Center. They’re trying to make life easier for caregivers by providing services. One of those unique services is providing a realistic stuffed animal that often distracts and preoccupies people with dementia. “My mom was prone to wandering, and she would get antsy," said Patty, who was a caregiver to her mom. "We’d give her her cat, and she was convinced it was a real cat, and it’s so life-like, it’s pretty amazing." As for Yvonne, here’s her advice for young adults: “Start not only thinking about your retirement benefits that are coming up but also think about long-term care. There’s insurance policies out there that you can purchase for a small amount right now.” For more information, head to the following websites: agingcarefl.org or seniorconnectioncenter.org

By: Anthony Hill

Reporter - WFTS Tampa Bay LARGO, Fla. — If you’re an older adult behind on your utility bill or have a broken air conditioner, your local Area Agency on Aging may be able to help. "Not too warm in here today,” said Ernest Back, looking at his thermometer. “It's only 81 degrees, 71% humidity because outside on the porch, it's 92 to 94 degrees," said Bach. Bach has been living in his Largo apartment building for 38 years and he knows first-hand the cost of paradise is rising. "It's been devastating to many in the low-income brackets and including senior citizens," said Bach. Bach said he went through two summers without an air conditioner before calling the Area Agency on Aging for assistance. They were able to help him buy a new $6,000 air conditioning unit through their EHEAP program. The program provides financial assistance to older adults who are past due on their utility bills or need a new air conditioner. "Thank goodness because the heat is repressive," said Bach. Many older adults, like Ernest, depend solely on their social security to survive, which means this program has helped many. "Seniors are having to make really difficult choices between paying their electric bill and buying food," said Ann Marie Winter with the Area Agency on Aging of Pasco-Pinellas. The organization knows for many of our area's older adults, forgoing an electric bill to save money is simply out of the question. "Seniors who need electricity to run their oxygen tanks, to run their CPAP machines must have electricity," said Winter. So, here are the requirements:

Original link to story can be found here. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed